Hey guys,

I’m working on an interesting project now. A repeat client has requested that I convert a cards game I previously made for them from Flash to HTML5.

As you may be aware, Adobe is discontinuing their Flash player browser plugin by the end of 2020.

There really aren’t any true “conversion” tools out there. In other words, say you have a Flash project that consists of a few Flash FLA files with library assets in them, and maybe some exported to external classes, as well as additional external asses loaded at run-time, as well as external AS3 files. And your build process (what you use to generate your final SWF file) uses either Flash CSx/Animate or say, FlashDevelop (good tool, by the way – I highly recommend it if you’re using Adobe AIR to build mobile games).

There is no conversion tool that can just convert all that into a HTML + JavaScript files with all the assets extracted from FLA files, and present you with an HTML index file that you can simply run and be on your merry away.

That. Would. Be. Awesome.

If you want to convert a Flash game to HTML5, you pretty much have to learn JavaScript if you don’t already know it, and rebuild it from scratch).

Depending on the simplicity of your game, you may get some help from Adobe’s Flash Animate, but I’ve never tried it, and due to the complexity of the games I make, it’s likely to not work.

There are several other tools out there, your best bet may be to simple rebuild the code, but you can still use the assets.

However, if you have the original source code – the ActionScript 3 .AS files, sounds, and Flash .FLA files (which I do have because I wrote the original Flash project in the first place) – you already have everything you need to do this. Meaning, you don’t need to go through the trouble of decompiling SWF files and other dubious tasks.

Also, fortunately, the Flash game I’m converting doesn’t do any blitting of bitmaps. All graphics are either bitmaps imported into the FLA, or vector art saves as library symbols. The library symbols can be converted to bitmaps so they can then be used in the HTML5 version.

The biggest challenge for assets and layout is no longer having a super-convenient WSYISYG (what you see is what you get) editor like Flash CS/Animate. This allows you to place and size the objects in a scene as they should look when the game is running. Without this vital tool, you have a few options:

1). Hard-code all the sizes and positions of everything, and references to what everything looks like. (OUCH! This is not the old days of game development. I’m pretty sure we can come up with something quicker and easier, right? 🤔 )

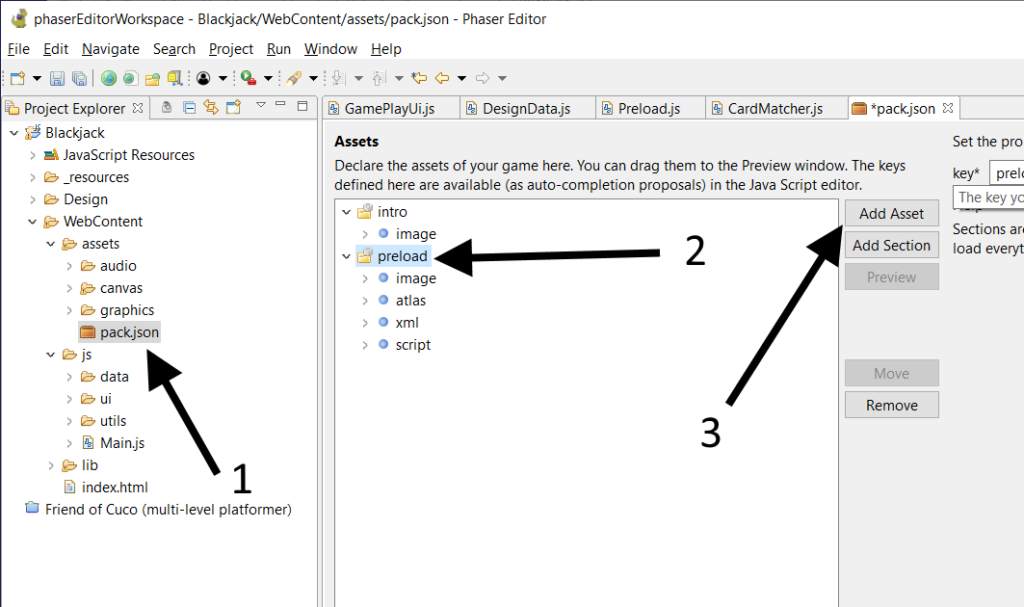

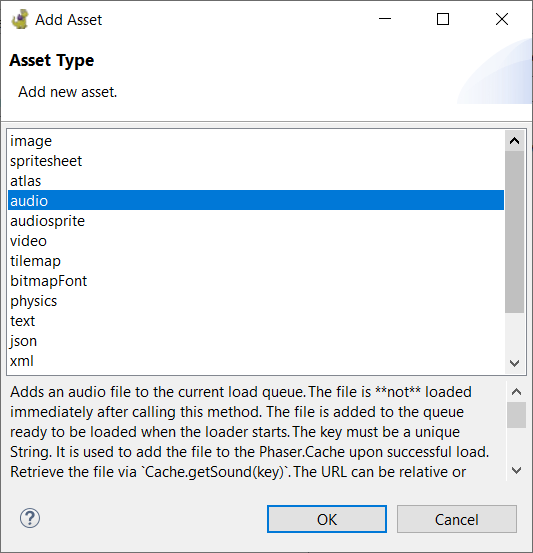

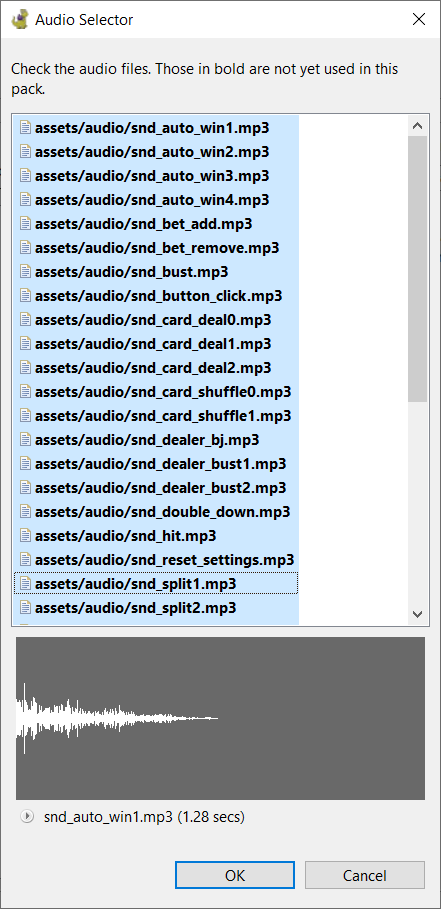

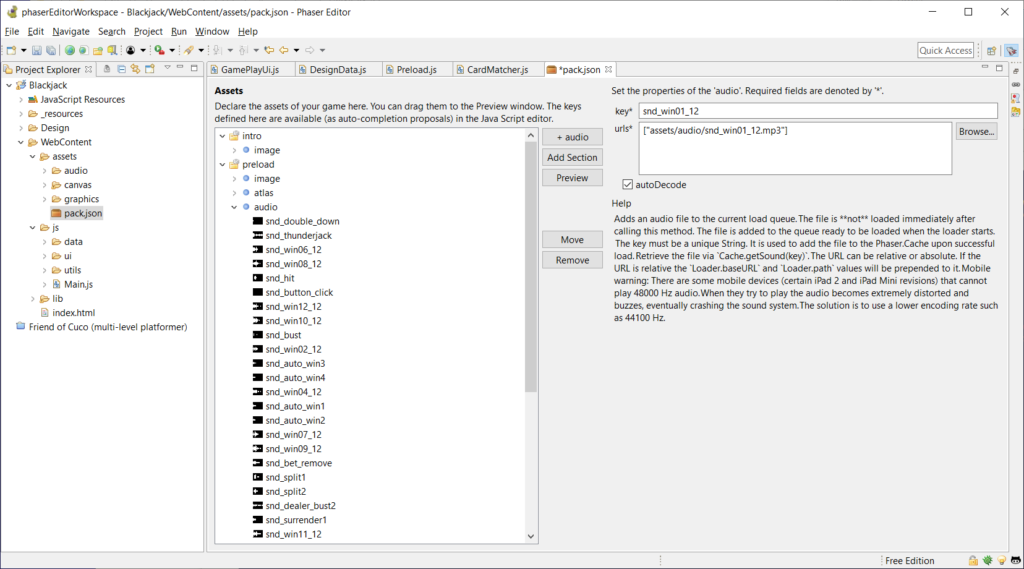

2). Use an editor, like Phaser Editor. A visual editor to build your layout, position and size objects on the scene. This editor has a built-in code Canvas Compiler that will translate your layout into JavaScript code, placing and sizing all your objects for you. You can then focus on building the layout. Now…

For the most part, converting AS3 to JavaScript files is fairly simple. Although it’s a laborious task of recoding, ActionScript 3 and JavaScript share many similarities, both having roots in the ECMAScript standards for example. Sure, you can’t just copy AS3 code, paste it into a JS file and call it a day, but if you know both languages well, the conversion process isn’t all that painful.

Here a quick example of an original source file written in AS3 for Flash, and below it, the JavaScript counterpart.

public final class EZ_PlayerData {

private var mvo_dailyScores:Vector.<BJ_DailyScoresData>;

private var mvo_cardsData:Vector.<EZ_PlayerCardsData>;

private var mn_betValue:Number;

private var mn_credits:Number;

private var mu_selectedHandIndex:uint;

private var mn_tournamentCredits:Number;

private var mb_isTournamentEnabled:Boolean;

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// ctor

public function EZ_PlayerData(u_maxHands:uint, u_maxCardsPerHand:uint) {

super();

mn_betValue = mn_credits = mn_tournamentCredits = 0;

mvo_dailyScores = new Vector.<BJ_DailyScoresData>();

mvo_cardsData = new Vector.<EZ_PlayerCardsData>(u_maxHands);

for (var u_index:uint = 0; u_index < u_maxHands; u_index++) {

mvo_cardsData[u_index] = new EZ_PlayerCardsData(u_index, u_maxCardsPerHand);

}

}

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// public functions

//==================================================================

// addDailyScore

//==================================================================

public function addDailyScore(o_score:BJ_DailyScoresData):void {

if (!o_score) {

return;

}

mvo_dailyScores.push(o_score);

mvo_dailyScores.sort(onSortDailyScores);

}

//==================================================================

// betValue (get)

//==================================================================

public function get betValue():Number {

return(mn_betValue);

}

//==================================================================

// betValue (set)

//==================================================================

public function set betValue(n_value:Number):void {

if (!isNaN(n_value)) {

mn_betValue = n_value;

}

}

//==================================================================

// cardsData (get)

//==================================================================

public function get cardsData():Vector.<EZ_PlayerCardsData> {

return(mvo_cardsData);

}

//==================================================================

// credits (get)

//==================================================================

public function get credits():Number {

return(mn_credits);

}

//==================================================================

// credits (set)

//==================================================================

public function set credits(n_value:Number):void {

if (!isNaN(n_value)) {

mn_credits = n_value;

}

}

//==================================================================

// getDailyScores

//==================================================================

public function getDailyScores():Vector.<BJ_DailyScoresData> {

return(mvo_dailyScores);

}

//==================================================================

// isTournamentEnabled (get)

//==================================================================

public function get isTournamentEnabled():Boolean {

return(mb_isTournamentEnabled);

}

//==================================================================

// isTournamentEnabled (set)

//==================================================================

public function set isTournamentEnabled(b_value:Boolean):void {

mb_isTournamentEnabled = b_value;

}

//==================================================================

// removeLastDailyScore

//==================================================================

public function removeLastDailyScore():BJ_DailyScoresData {

return(mvo_dailyScores.pop());

}

//==================================================================

// selectedHandIndex (get)

//==================================================================

public function get selectedHandIndex():uint {

return(mu_selectedHandIndex);

}

//==================================================================

// selectedHandIndex (set)

//==================================================================

public function set selectedHandIndex(u_value:uint):void {

mu_selectedHandIndex = u_value;

}

//==================================================================

// tournamentCredits (get)

//==================================================================

public function get tournamentCredits():Number {

return(mn_tournamentCredits);

}

//==================================================================

// tournamentCredits (set)

//==================================================================

public function set tournamentCredits(n_value:Number):void {

if (!isNaN(n_value)) {

mn_tournamentCredits = n_value;

}

}

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// private functions

//==================================================================

// onSortDailyScores

//==================================================================

private function onSortDailyScores(o_score1:BJ_DailyScoresData, o_score2:BJ_DailyScoresData):Number {

if (o_score1.score >= o_score2.score) {

return( -1);

}

return(1);

}

}

And here is the corresponding JavaScript code:

(function(global) {

global.Multiplay = global.Multiplay || {};

Multiplay.PlayerData = Multiplay.PlayerData || {};

//===========================================================================================

//"public"

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

//ctor

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Multiplay.PlayerData = function(u_maxHands, u_maxCardsPerHand) {

this.dailyScores = [];

this.betValue = 0;

this.credits = 0;

this.selectedHandIndex = 0;

this.tournamentCredits = 0;

this.isTournamentEnabled = false;

this.cardsData = [];

for (var u_index = 0; u_index < u_maxHands; u_index++) {

this.cardsData.push(new Multiplay.PlayerCardsData(u_index, u_maxCardsPerHand));

}

};

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

//addDailyScore

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Multiplay.PlayerData.prototype.addDailyScore = function(dailyScoreData) {

if (!dailyScoreData) {

return;

}

this.dailyScores.push(dailyScoreData);

this.dailyScores.sort(this._onSortDailyScores);

};

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

//removeLastDailyScore

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Multiplay.PlayerData.prototype.removeLastDailyScore = function() {

return(this.dailyScores.pop());

};

//===========================================================================================

//"private"

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

//_onSortDailyScores

//-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Multiplay.PlayerData.prototype._onSortDailyScores = function(score1, score2) {

if (score1.score >= score2.score) {

return( -1);

}

return(1);

};

})(window);

AS3 takes the usual object oriented programming approach with classes, by defining an actual ‘class’, its constructor, and added properties and methods onto that class.

JavaScript uses protoypes, and a function of the same name as the “class” acts like a constructor. You then add functions onto the prototype which act like the class’s methods.

Due to the absence of public getter/setter properties, the JavaScript file turned out to be way shorter than the original ActionScript. However, you have to be careful when accessing members of the Multiplay.PlayerData prototype, that you don’t accidentally modify a member intended to be treated as private. In JavaScript, I precede such functions and members with an underscore ( _ ).

Throughout the conversion process, I highly recommend that you constantly test the code in small updates to ensure that the code is working as expected (much like you would when building any game, but especially here). I convert AS3 classes as few as possible at a time, then re-test for errors.

How Phaser Editor Helps

Other than the aforementioned benefits of using a WSYIWYG editor, Phaser Editor also allows you to write custom code in the same files that it creates with its canvas compiler.

In most cases, I prefer to keep the UI code separate from logic/business/implementation code, adapting some concepts from Model View Controller design pattern. This makes it easier for me to convert classes from AS3 to JS, since the UI and logic code will be implemented different in the two scripting languages.

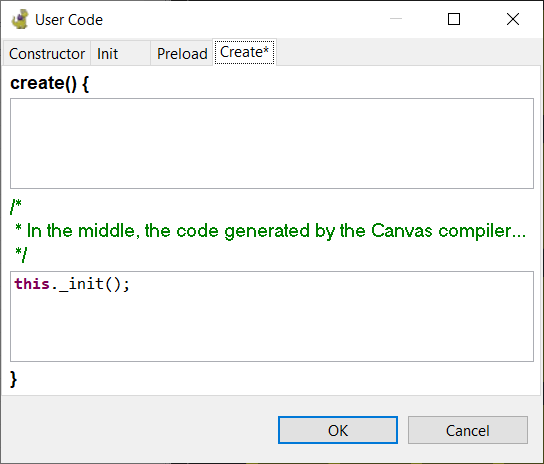

That said, in the files generated by the Phaser Editor canvas compiler, I can add an “initialization” method call the editor’s User Code section, and from there, set up all the UI objects that were created on the canvas.

This one line is the only one I write in the Create tab of the User Code dialog. I prefer to keep code in here minimal and focus on write what the _init does in the user code section of the canvas JS file. Phaser Editor will reserve areas of the JS file as user code for you, and the code there will not be overwritten the next time you save the canvas layout (which will cause the canvas compiler to update the corresponding JS file, overwriting any unsaved changes – make sure you always save your JS file first before going saving new changes in the editor’s canvas!)

In the “user code here” section of the JS file (marked by Phaser Editor in a commented at the bottom of the file), I defined an empty _init function. This is where you can custom setup any UI objects, and we’ll be revisiting this later.

GameView.prototype._init = function () {

};

Converting a Button

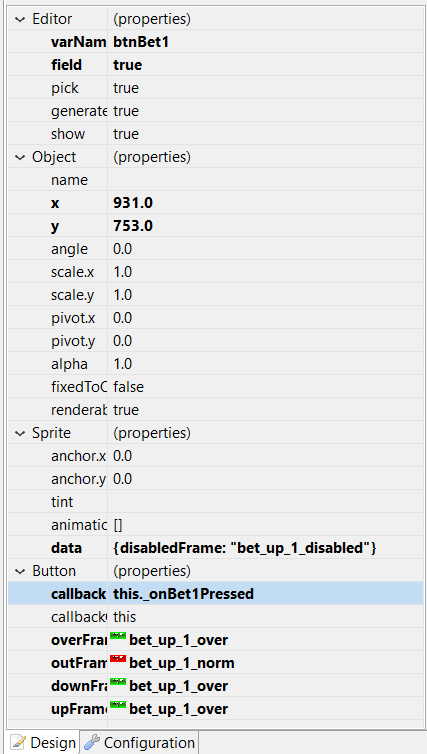

Next, say I want to create (or “re-create”, as we’re rebuilding the original Flash layout 😉 ) a button on the canvas named btnBet1 (from the casino cards game I’m converting for my client). Because I also have the field property set to true, the canvas compiler will create a property on the JavaScript file of the corresponding canvas called fBtnBet1. I also have the callback property set to a method on this instance of the canvas object this._onBet1Pressed. In my user code, I can define the _onBet1Pressed function. You’ll also want to add the button frames for over, out, down, and up so your button can respond to the various button states.

The canvas file is actually a Phaser state, and the canvas compiler will automatically generate the following code in the state’s create method:

var _btnBet1 = this.add.button(931.0, 753.0, 'some_atlas', this._onBet1Pressed, this, 'bet_up_1_over', 'bet_up_1_norm', 'bet_up_1_over', 'bet_up_1_over', _buttons);

...

this.fBtnBet1 = _btnBet1;

In the user code section of the JS file, I can create the button pressed callback function like this:

GameView.prototype._onBet1Pressed = function () {

};

It’s similar to a MouseEvent handler from ActionScript 3 when setting up a button to respond to mouse clicks.

Keeping the UI code and implementation code separate, I won’t include what the button actually does inside this method. Instead, I’ll have it dispatch a notification, via a Phase Signal. I treat the signal is treated as a public property of the canvas object, and I define the signal in the _init method created earlier:

GameView.prototype._init = function () {

this.onBetButtonPressed = new Phaser.Signal();

};

When the button is pressed, I want that signal to fire a notification to be handled by the implementation code. Modifying the _onBet1Pressed function, it now looks like this:

GameView.prototype._onBet1Pressed = function () {

this.onBetButtonPressed.dispatch();

};

There is no logic code in this canvas JS file, since it’s for UI only. The implementation is handled by the code that processes the game logic. First, it assigns a function to be handled by the signal when it dispatches a notification:

var gameView;

...

gameView.onBetButtonPressed.add(function() {

//do whatever when the button is pressed

});

Instead of inlining the function, you can also pass in a function reference:

gameView.onBetButtonPressed.add(onBetBtnPressed);

...

function onBetBtnPressed() {

//do whatever when the button is pressed

}

That’s pretty much how all the buttons will be converted.

Converting Fonts

Fonts is a big one. In Flash, you can embed fonts directly into the SWF file to make sure that the fonts will show up, even if the fonts aren’t installed on the end users’ machines. However, you can’t do this with HTML5. Instead, you have to either use web fonts something like this, or you can use bitmap fonts. Phaser Editor can not show all the fonts installed on your system. A quick excerpt from this page about fonts in Phaser Editor:

Phaser Editor uses JavaFX to render the scenes but Phaser uses the browser for the same purpose. This means that in some cases the text object is not rendered in design-time like Phaser renders it at run-time.

Note that Phaser Editor can use the fonts installed in the OS, but the majority of them are not available in all platforms, so we recommend to use safe fonts or load the font files in the CSS of your game.

I decided to go with using Bitmap fonts. Phaser Editor also supports bitmap fonts. This means, I have to create a texture atlas and corresponding XML for all the fonts I want to use. There are a few tools out there for this task:

For this project, I went with the Generator. While it’s not as powerful as Littera in terms of customizations, because it supports font formats other than only True Type. And this game does use some True Type fonts, and I want to be as faithful to the original implementation as possible.

A quick note on using the Generator. When it creates your text image atlas, you’ll also get a .FNT data file. This is the XML file that Phaser (and Phaser Editor) uses when setting up bitmap fonts. You can simply rename the extension from FNT to XML, and you should be good.

That’s the jist of what I’ve done, and so far, I’m not running into any major hurdles. It’s just a detailed process, and you should convert and test in small increments. I may write future updates to this if I encounter anything that warrants an article. I’m thinking timeline animations, but because I didn’t use any in this game, I don’t expect any issues there.

That’s all for now guys. Thanks, and I’ll talk to you next time. Take care!

– C. out.